When students, educators and administrators return to school after the COVID-19 school closures, classrooms will be a changed landscape. While it is difficult to speculate on what missing months of school may mean for student achievement, research on seasonal learning and summer learning loss can offer some insights that can help state leaders understand, plan for and address some potential impacts of this extended pause in classroom instruction.

Possible Outcomes of Coronavirus School Closures

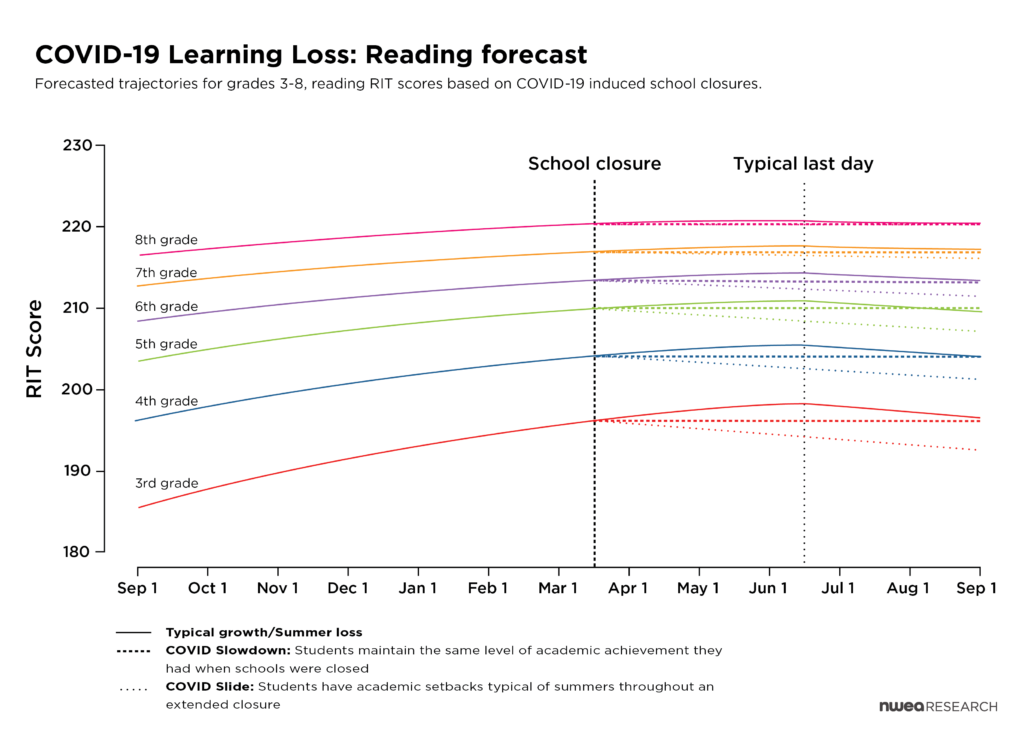

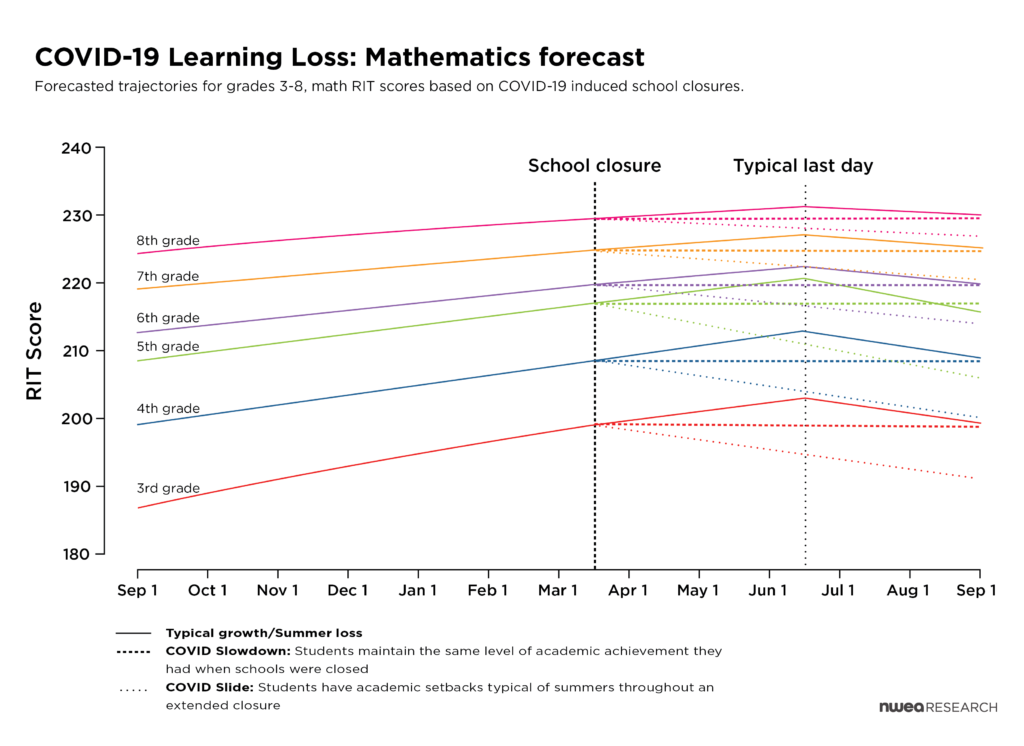

NWEA projects that current school closures could result in substantially lower achievement levels for students. Using a national sample of over 5 million students who took MAP® Growth™ assessments in grades 3-8, researchers estimated the potential impact of COVID-19 related school closures on student learning. NWEA researchers compared academic achievement trajectories during a typical school year for grades 3–8 where no disruption to learning took place to two scenarios that could result from school closures:

- A COVID-19 slide, in which students show patterns of learning loss typical of summers throughout the extended closures.

- A COVID-19 slowdown, in which students maintain the same level of academic achievement they had when schools were closed (modeled for simplicity as beginning March 15) until schools reopen.

Preliminary estimates suggest impacts may be larger in math than in reading and that students may return in fall 2020 with less than 50% of typical learning gains and, in some grades, nearly a full year behind what NWEA would expect in this subject in normal conditions.

NWEA provides caution around these projections. While the COVID-19 school closures have some characteristics in common with a summer break, many school systems and families across the country are implementing various online curriculum, instruction and progress monitoring resources to offset the disruption. However, trauma, joblessness and an increase in the number of families facing food insecurity, homelessness, domestic violence and even the illness or death of a loved one could make academic projections even bleaker for the nation’s most vulnerable populations.

What States Can, and Are, Doing

These academic forecasts trigger critical questions for state leaders: How do they support educators and families during and after the COVID-19 crisis? What can they do to mitigate these academic projections? To start:

- Address immediate needs: Invest in technology required to close the digital divide, in addition to curriculum and instruction programs and tools to support districts in facilitating as much learning as possible between now and the fall. Focus on math, where losses are likely to be greatest, but not at the expense of reading. Consider implementing policies and programs that support learning throughout the summer. Examples of what states have done:

-

- Kansas: To provide continuity of learning outside of typical school practices, the Kansas Continuous Learning Taskforce provides explicit guidance and protocols for a variety of stakeholders leading school districts in the context of COVID-19. For example, the guidance document includes essential questions for school administrators and a professional learning plan for educators.

-

- South Carolina: In an effort to immediately meet the connectivity needs of students as the state transitioned to remote learning, the South Carolina Department of Education deployed 3,000 school buses with Wi-Fi access, prioritizing rural and high-poverty districts.

- Invest in contingency planning: Develop policies and practices to prepare for another school closure in the fall and/or beyond. Determine what is critical to teaching and learning and how to make it virtually available. Address challenges you have not yet been able to attend to, such as accessibility, special education needs and differentiated instruction. Fund additional resources required to ensure that families who are economically or socially disadvantaged are not disproportionately impacted by another closure. Examples of what states have done:

-

- Florida: In late March, Florida Virtual Schools created a new online learning community for families and teachers to better understand how to support students’ online learning experiences. The free digital resource provides videos and information that districts across the state can use to better understand virtual learning formats, especially during such an overwhelming time.

-

- Illinois: To garner understanding of the barriers to e-learning in the state, the Illinois State Board of Education conducted a technology needs survey where districts indicated what they would need to move to a 1:1 environment for all grade levels and ultimately provide comprehensive online learning to students. To fund follow-up efforts to remove identified barriers, ISBE is collaborating with the governor’s office and philanthropic community.

-

- Massachusetts: To provide early guidance for supporting special education students through the COVID-19 school closures, the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education released an FAQ for schools and districts. In addition to other supports, the department provides recommended educational resources for students with disabilities.

- Partner with districts on restart plans: Access trusted research of student learning patterns to inform policies, programs and practices that will support efficient recovery of lost learning. Support districts that have had to focus their budgets on instructional technology and resources by providing formative instructional tools and interim assessments that will help teachers identify where each student is when schools reopen in the fall. Explore how data from interim assessments can help state and district leaders assess statewide impacts of COVID-19 on learning and track progress in catching students up — an effort likely to span several years. Consider providing professional learning to help teachers and leaders interpret and use data to inform decisions about how best to structure instruction and resources to maximize classroom time.