A major part of the Arts Education Partnership’s work in the past six months has been focused on its new strategic mission and engagement strategy. These documents articulate how AEP — including its 114 partner organizations — can add value to the work of Education Commission of the States and maximize its position to inform and elevate the work of partners. Current partner organizations collectively work at every level of the education sector from birth through adult learning, in schools and communities and in every art form; and they have deep experiences in all facets of education to share with policymakers.

Strategic Mission

When I started my tenure as AEP director in October 2019, I knew the organization’s guiding 2020 Action Agenda would need to be refreshed. This document had served as the framework under which AEP’s work was organized since its adoption in 2015.

Education Commission of the States and AEP solicited feedback from partner organizations on a refreshed guiding document, and AEP has updated our strategic mission with this feedback in mind. I’d like to highlight a few key parts of that strategic mission.

First, the new strategic mission statement — around which AEP is organizing all its work — is:

AEP is the nation’s hub for arts and education leaders, building their leadership capacity to support students, educators and learning environments. Through research, reports, convenings and counsel, leaders gain knowledge and insights to ensure that all learners receive an excellent arts education.

The 2020 Action Agenda had four pillars related to supporting students, educators, leaders and learning environments. The new strategic mission focuses AEP’s work on building leadership capacity for arts and education leaders. The remaining three pillars represent the ways in which partner organizations do their work.

Second, the strategic mission aligns AEP’s products and services to Education Commission of the States’ research, report, convene and counsel framework. This framework allows AEP to more clearly describe the ways in which its partners and others can engage in the work.

Third, in response to feedback from partner organizations, AEP made a deliberate choice in the strategic mission to use “arts education” to describe all learning facilitated by AEP partners. This includes in-school experiences with certified arts teachers, arts integration experiences with general education teachers and/or teaching artists, and community-based arts learning experiences. AEP has been using the framework outlined in Americans for the Arts’ 2014 publication “A Shared Endeavor: Arts Education for America’s Students" to help describe arts education in these varied contexts.

Engagement Strategy

In addition to the strategic mission, the new engagement strategy outlines expectations for how AEP interacts with partners and how partners interact with AEP. The guiding principle in the development of this document is that information should be bi-directional: Partners should share information and expertise with AEP, and AEP should share information and expertise with partners. There are a few key changes outlined in the engagement strategy that AEP hopes will provide clarity and invite more arts education leaders to engage.

First, criteria for becoming a partner organization focus on organizations that do work at a national level or that focus on systems change. AEP defines “systems change” as working to change institutional structures and behaviors, public attitudes, cultural norms, policy decisions and/or resource allocation in order to support equitable access to arts education for all learners, especially those who have historically been marginalized by systemic racism and inequalities.

Next, there is a new affiliate category for organizations and individuals who aren’t working nationally or at the systems-change level. For example, these could be organizations doing direct service work in their local communities or emerging groups who would benefit from connections to people doing similar work.

Finally, AEP more clearly outlined both the benefits and responsibilities of partnership. There are new benefits for becoming a partner — like accessing the early-bird registration rate for the AEP Annual Convening up to the event start date — and new opportunities for engagement. Engagement activities could be partners contacting AEP staff members to request a speaker or facilitator for an event, co-authoring a conference session proposal or collaborating on a publication.

As a reflection of both the strategic mission and engagement strategy, AEP created a What We Do page on its website so partners, affiliates and others know how they can collaborate with AEP and with each other. AEP hopes the clarity this page brings to its products and services, along with a revitalized strategic mission and engagement strategy, sets the tone for future work.

AEP looks forward to bringing its new guiding documents to life!

Did you know that Nevada has arts education instructional requirements for K-12 public schools, youth centers, state facilities and detention centers? Neither did I, until I joined the team at the Arts Education Partnership and began working on ArtScan. As part of AEP’s new work exploring the arts across the juvenile justice system, I’ve been researching what arts education opportunities are available for justice-involved youth and found through ArtScan that Nevada is one state addressing this topic.

This is just one example of the breadth of information included in ArtScan, the nation’s clearinghouse of the latest state policies supporting arts education from all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

ArtScan, an easy-to-use database, includes up-to-date information on 14 policy areas related to K-12 arts education such as standards, instructional requirements, graduation requirements, assessment, state accreditation, teacher-licensure requirements and funding. Each year, in collaboration with the State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education (an AEP partner organization), AEP updates this database and provides multiple ways for users to explore the data:

ArtScan also allows a user to see a comprehensive 50-State Comparison across specific policy areas.

New in 2020

All 50 states and the District of Columbia have adopted arts education standards for early childhood, elementary and secondary education, and many state boards have recently updated them. Here are some of the updates captured in ArtScan this year:

Navigating ArtScan reveals many changes in policies related to arts education across the country. From expanding language to include new art forms, to teacher credentialing and arts requirements, ArtScan is your one-stop shop for information that can help ensure that all students have access to an excellent arts education. Explore arts education policies in your state and compare with others!

Research has found that adolescence is a time when students begin to think more abstractly, learn through teamwork and have a desire to explore topics they find interesting. Additional research suggests that middle school is a time when students can benefit the most from career exploration. Given where adolescent children are developmentally, there is an opportunity for students to develop employability skills and gain a sense of their interests through career exploration in middle school and early high school.

There are a series of ways that states have developed and supported career exploration and career and technical education opportunities for middle school students. Generally, states have considered policy and state action to foster and support early CTE and career exploration. The policy and state action include:

Creating CTE and Career-Exploration Opportunities in Middle School

Some states have adopted policy that expands and supports offering CTE courses and career exploration in middle school. Depending on the structure of the program or course offerings, students can learn about employability skills, connect academic interests and classroom learning with potential careers, and begin the process of identifying and planning for learning opportunities in high school. States that have adopted expansion of CTE and career exploration to middle schools have worked to align standards and systems across middle school and high school programming to allow students to build on their early exploration and coursework.

In 2014, the Ohio legislature enacted legislation that requires schools to provide CTE courses in middle school. The offered courses are primarily introductory or exploratory courses aligned with high school CTE courses through state-level standards. The state has allowed licensed teachers to lead most middle school CTE courses. The state department provides a range of resources for schools, including outlines for each middle school course.

Requiring CTE or Career-Oriented Course Completion in Middle School

In addition to offering CTE courses and exploration experiences, states have adopted policy that requires students to take CTE courses or engage in career-exposure experiences that are offered in middle school. In some instances, the requirement connects broader CTE or career standards to academic and career plans for the students.

Virginia statute requires that each school board require each middle school student to take at least one career-investigation course or engage in an alternative activity that allows for career exploration. The course or alternative experience must provide a foundation for the student to develop their academic and career plan. The state board of education is required to develop content standards for the career-investigation course and experiences.

Requiring Personalized Education and Career Plans Beginning in Middle School

Some states have implemented requirements for career and academic planning. Generally, the plans provide an opportunity for students to identify their interests and possible opportunities they can pursue to reach academic and career goals. While plans do not necessarily lead to career exploration for all students, the planning process can allow students opportunities to identify and pursue experiences based on their interests.

In 2013, Wisconsin passed legislation to provide continual funding to implement and support academic and career advising statewide. State statute requires that all students in grades six through 12 receive academic- and career-planning services. The department of public instruction provides and maintains technology and computer programs to support districts in providing academic and career planning to students. Also, the department provides guidance and technical assistance to school districts, teachers and counselors on how to provide academic and career plans for students.

While research demonstrates a benefit of early career exploration and states have developed policy that supports the creation and offering of career exploration, there are some notable barriers associated with providing access to early career exploration across a state. As states consider increasing early career exploration, there are opportunities to address the barrier while creating more opportunities for students.

Last month, Education Commission of the States President Jeremy Anderson shared six trending education policy topics we will likely see in 2020. Arts education stakeholders and advocates may not be surprised to see that the arts were not listed among the top education issues — but don’t worry! The arts interact with these topics in meaningful ways and can be a critical part of the dialogue around the top six trending education policy priorities.

Early childhood education: From funding to literacy development, we are seeing policymakers’ attention shift to early learners. Research demonstrates that arts integration improves literacy and school-readiness skills for preschoolers in underserved communities, and exposure to the arts at an early age impacts the development of students’ attitudes toward the arts. The arts are also strongly linked to the development of social skills and emotional regulation for early learners.

School climate: Policymakers are addressing school climate through multiple approaches, including student mental health, culturally responsive curricula and school discipline alternatives. Participation in the arts has been found to have a positive effect on student behavior and school engagement, and culturally responsive teaching through the arts improves student connection to the content and their own identities.

K-12 funding: All 50 states and the District of Columbia have adopted arts education standards for early childhood, elementary and secondary education; and more than 40 states have adopted policies related to instructional requirements for elementary, middle and high school. Fewer than 25 states have adopted policies that develop a statewide arts education grant program, though at least 10 states fund arts education through the state education agency.

Teaching: In 2019, policymakers enacted 281 bills affecting teachers. Forty-five states require arts teachers to be endorsed, licensed or certified in one or more arts disciplines; and 27 states specify arts requirements for non-arts teachers. At least 17 states include the arts in alternative certification pathways for teachers.

College affordability: States have continued the effort to support students in paying for college, and arts education organizations have also made efforts to connect students to college and scholarship resources. Dual enrollment arts courses allow high school students to earn college credit, saving money in the long term. High-achieving students across dance, theater, music and visual arts are also recognized through honor societies that provide opportunities for scholarships and college preparation. There is not yet a similar organization for media arts.

Workforce development: By 2030, 85% of the jobs that today’s K-12 learners will be doing haven’t been invented yet. The arts are uniquely situated to teach transferable skills required for career success — such as communication, problem-solving and collaboration — that will continue to be in high demand by employers. In arts environments, learners have the chance to practice active learning, cultural competence and other skills necessary for the workplace of the future.

While 2020 is probably not the year that we see arts education as a national policy priority, let’s not forget that arts education is education — and it is connected to the education policy landscape in meaningful ways.

Want to continue this conversation?

The Arts Education Partnership is pleased to collaborate with Americans for the Arts to host the Arts Education Policy Briefing on March 29 in Washington, D.C. AEP invites you to join to discuss two of these priorities — workforce development and school climate — together with other education and arts stakeholders. Registration is open, and we look forward to seeing you there!

State leaders, including Wyoming’s State Superintendent of Public Instruction Jillian Balow, are learning that access to technology alone does not guarantee improved pedagogy. Access must be matched by efforts to build educators’ capacities to provide meaningful learning experiences for all students. Wyoming strategically invested in educator development by leveraging a research-based framework on effective technology use. Below, Balow shares how Wyoming led this process and her advice for other leaders.

State leaders, including Wyoming’s State Superintendent of Public Instruction Jillian Balow, are learning that access to technology alone does not guarantee improved pedagogy. Access must be matched by efforts to build educators’ capacities to provide meaningful learning experiences for all students. Wyoming strategically invested in educator development by leveraging a research-based framework on effective technology use. Below, Balow shares how Wyoming led this process and her advice for other leaders.

How did Wyoming recognize the need to build educator capacity around effective ed tech use?

In 2016, Gov. Matt Mead launched the Wyoming Classroom Connectivity Initiative to establish the infrastructure necessary for digital learning. This interagency effort provided supports for districts using E-Rate and exponentially increased the number of connected classrooms. We observed a “we can do it” mentality permeate throughout the state, as local leaders saw neighbors making strides. But what kept me up at night was that, despite our progress, there remained educators who only considered technology as useful for administrative tasks like grading.

Educator capacity has implications for equity. When properly trained, educators can empower students through technology to have agency in their learning. To better understand how to manifest this vision, we surveyed hundreds of district and school staff about their needs. We learned that stakeholders agreed on the importance of digital learning opportunities for student success and the benefits of professional development on integrating technology into instruction. This information was used to develop a statewide digital learning plan, which outlines how the state will systematically help educators use technology effectively.

Which policies and partnerships have been instrumental in helping build educator capacity?

I’m fortunate to work with colleagues who recognize the urgency of this issue. Together, we directly integrated the ISTE Standards into state content standards to show educators how technology can enhance learning in various subjects. We also adapted the ISTE Standards into our own digital learning guidelines, which map specific student skills and make recommendations for leveraging the ISTE Standards across grade bands.

Another incredible resource was ISTE’s 2019 roundtable for state chiefs, where I learned how other leaders were navigating the educator capacity issue. One strategy that stood out was ISTE Certification, designed specifically to support mastery of the ISTE Standards. With ISTE’s help, we worked to implement this rigorous program in Wyoming. We located a regional provider through an RFP [request for proposal] process and leveraged ESSA [Every Student Succeeds Act] Titles II-A and IV-A funds to enroll 100 educators. Our Professional Teaching Standards Board voted to qualify ISTE-certified educators for the state’s instructional technology endorsement. For the first time, Wyoming educators are permitted to earn a new endorsement without going through a postsecondary program.

How will the state sustain the development of educator capacity?

The value of ISTE Certification for Wyoming educators is that it provides a pathway for sustainability. The program is focused on improving pedagogy, rather than using a specific tool. Therefore, the practices learned can be applied in different contexts. ISTE-certified educators can also propagate effective technology use throughout their school communities, which is especially helpful for educators whose preparation programs did not train them on technology-enhanced pedagogy.

What advice do you have for other states engaging in this work?

The good news is, you don’t have to be a technology pro to begin this work and you don’t need to do it alone. State leaders must make this work a priority by developing a strategic plan in collaboration with experts within their agencies, external partners and stakeholders. Engaging these different groups will help you strategize and implement an impactful educator development model that effectively meets the needs of those directly supporting students every day.

High school students in three states — Illinois, Louisiana and Texas — already or will soon face a new graduation requirement: completion of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid. Lawmakers in at least another five states plus the District of Columbia are currently considering similar legislation — and it’s only February.

The simplicity of the policy is part of its appeal: If the FAFSA were a requirement for graduation, presumably, more students would complete the form, learn of aid availability and matriculate on to postsecondary education. Here at Education Commission of the States, we are learning all the time about what states can do to help preserve and leverage this simplicity into increased rates of college-going.

Specifically, states considering a similar change may benefit from considering these questions as their policies are developed:

While this list of questions is certainly not exhaustive, it provides the broad contours of a policy that can provide uninterrupted access to the high school diplomas students have earned, while still increasing rates of aid applications and taking steps to ensure that students have the financial information they need to make decisions about postsecondary education.

To help states begin to answer these questions and learn from other states’ approaches, Education Commission of the States hosted a webinar, where attendees learned about the states that have enacted or are considering policies across this topic. The webinar also included representatives from the Louisiana Office of Student Financial Assistance, who have worked collaboratively to enact and implement this change in their state. View the full webinar here.

A director of a state office of early learning inquired about early childhood integrated data systems. Our response includes an overview of state early childhood integrated data systems and state examples. The response also includes a breakdown of the types of data states collect and report and state data governance structure models.

To provide timely assistance to our constituents, State Information Requests are typically completed in 48 hours. They reflect an issue scan versus a comprehensive analysis.

Graduating a higher percentage of students may depend on how colleges address fundamental student needs — such as secure housing; reliable access to nutritious food; and affordable, flexible transportation that can swiftly ferry students between school, work and home. This seems like a tall order — and it is. However, recent research on food security from Trellis suggests that this basic need may not be intractable; instead, this latest study shows that food security fluctuates, with ebbs and flows throughout the school year. Understanding the dynamics behind these shifts can guide interventions that stabilize students’ basic needs and allow them to achieve their educational potential.

To capture this insight, the Trellis research team undertook an ambitious longitudinal study, which followed 72 students for nine months and resulted in 499 interviews concerning the effects of student finances on academic performance. The first report from this effort is “Studying on Empty: A Qualitative Study of Low Food Security Among College Students.”

Of 72 student participants, 36 experienced either low or very low food security — based on the six-question scale used by the U.S. Department of Agriculture — at some point during the study. This prevalence may surprise some, but is still slightly lower than the finding from the Trellis’ Fall 2018 Student Financial Wellness Survey (56%). Remarkably, each of those 36 students saw their food security fluctuate during the study. Let’s look at one student to illustrate how these shifts can occur. We’ll call her “Molly” to protect her identify.

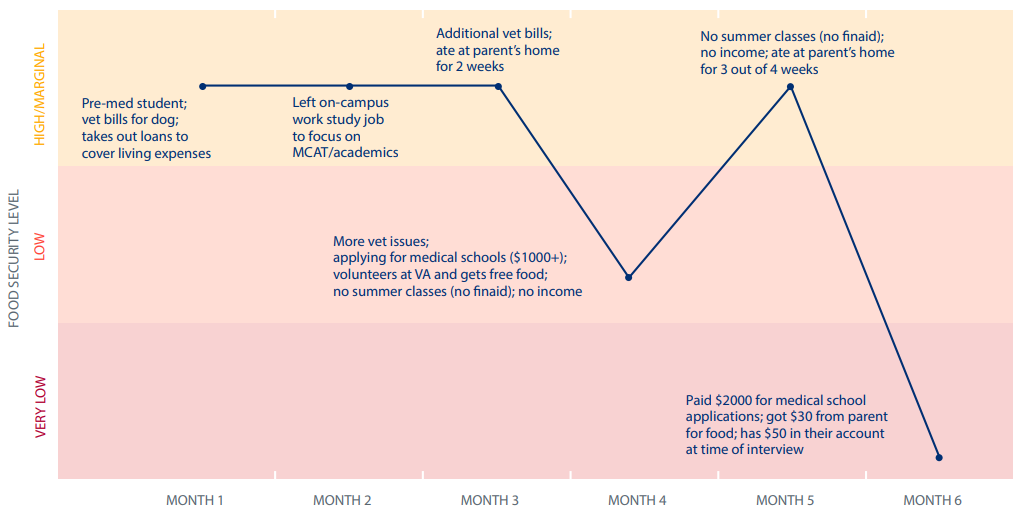

Molly was food secure for the first three months of the study and had a restrictive, but attainable, budget. This changed in the fourth month, when her food security dropped from high/marginal to low because of unexpected expenses and a loss of income as she tried to concentrate on academics. Molly secured free food through volunteering efforts and from staying with her parents over the summer. This temporarily increased her food stock, but without additional financial aid or a regular source of income, her food security degraded to very low. By the sixth month, Molly nearly drained her savings paying over $2,000 in medical school applications; and although she received $30 from a parent for food, she had only $50 in her bank account at the time of the last interview. This left her vulnerable to the next financial shock — which, she feared, might force her to abandon her educational aspirations.

“Molly’s” Six-Month Food Security Experience

The Trellis study identified four major catalysts for improving food security:

Molly’s difficulties were not readily apparent to her college; such visibility requires school administrators to be trained to identify signs of poverty and then be prepared to act quickly to address emergencies. Such colleges typically adopt some of these measures to restore basic needs security on their campus:

Trellis hopes that by showing how food security can decline or improve, policymakers can craft policies that help guide colleges and university systems to promptly respond to problems that threatens students’ educational ambitions.

All states have rural districts and schools and must contend with barriers that prevent equitable and adequate education for all. In fact, in 23 states, more than 20% of students attend a rural school. Research shows that rural schools face many of the same challenges as urban schools, albeit in a different context: High levels of poverty negatively affect property tax revenue, an educational achievement gap between racial and ethnic groups remains, and it’s difficult for schools to recruit and retain good teachers. Indeed, teachers are expected to do more with fewer resources in rural schools.

One way states attempt to address these challenges is by increasing the amount of money rural schools receive through funding formulas, specifically with small school size and isolated school funding adjustment policies. According to our recent 50-State Comparison on K-12 Funding, 29 states have a small size or isolated adjustment policy in statute.

Small and isolated schools

Statutory definitions for each policy vary state by state. Generally, small schools and districts refer to those with low enrollment numbers within a set range (under 100 students is a common threshold). While in many instances small schools are also isolated schools, not all isolated schools are necessarily small schools.

Isolated schools and districts indicate geographic isolation or a need for increased resources to provide an adequate and equitable education, compared with non-isolated schools and districts. States identify isolated schools and districts based on whether they meet one or more of the following factors:

Small school and district funding

Funding for small schools and districts depends on a state’s funding formula. Some states provide extra funds to schools below enrollment, while others use teacher-to-student ratios. For example, Alaska provides additional funding by allowing districts to increase their enrollment count. The amount of the adjustment to the enrollment count decreases as the school size increases, providing more funding for smaller schools. In South Dakota, additional funding for small schools is calculated by adjusting the target teacher ratio based on enrollment.

Isolated school funding

After states identify a school or district as isolated, they adjust the funding formula to allocate additional funds accordingly. They provide funding either on a sliding scale, based on the size of the school or district, or based on the budgetary discretion of the legislature. However, some state isolation funding adjustment policies cap additional funds for schools based on how large a school or district is. Arkansas, for instance, provides additional funding for isolated school districts that meet certain geographic and sparsity criteria but limit a district’s eligibility based on an enrollment threshold.

Click here if you missed the other blog posts in this series. If our team at Education Commission of the States can help as you work on your state’s K-12 education funding system, feel free to contact us.

While 2020 is inherently a big election year because it includes a presidential race, it is also a big election year for states: 11 states (plus American Samoa and Puerto Rico) are holding governors races, and 86 legislative chambers across 44 states have seats up for election.

Copyright 2025 / Education Commission of the States. All rights reserved.