Every morning at the public high school across the street from my home, students show up from a few different neighborhoods: the middle income section that I live in, larger homes a few miles north and a small trailer park located about a mile south. While each of these students is different, none of them file a form asking about their income or family assets before they show up for first period biology. Our system of universal, publically-funded high school education makes this a reality.

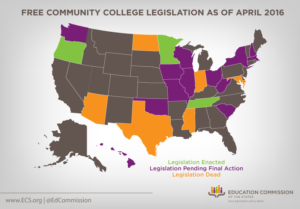

Researchers and policymakers have begun to question, however, whether universal access to education should end at age 18. Nearly half of the states have considered measures to enact free college programs for resident students. At their core, these proposals frame cost as the primary barrier to postsecondary enrollment, and one that federal and state policy should eradicate.

The use of the word “free” in the context of postsecondary education hasn’t come without controversy- some say community college is already free for Pell-eligible students, some say it shouldn’t be universally free at all, and some say that the ongoing economic and democratic health of our nation hinges on the passage of these proposals.

At the state level, however, “free college” proposals share more common attributes with existing state-funded financial aid models than universally-provided public secondary education.

- Limiting eligibility to students directly from high school

By and large, the majority of free community college proposals across the states would disproportionately benefit students matriculating directly from high school to college. About a third of the proposals across the states specifically link eligibility to the high school completion date, ranging anywhere from the fall term immediately following high school completion (i.e. Illinois), to six months (i.e. Oregon), to up to two years (i.e. Maryland.)A preference for subsidizing the cost of a “traditional” college experience is also seen in the enrollment requirements. In many of the proposed models, full-time enrollment is required, commonly defined as 12 credit hours (i.e. Oklahoma and Missouri.)

- Using existing state-aid systems and oversight

In many of the proposed programs, state-level oversight of the program rests with an existing state agency already tasked with state financial aid program administration (i.e. Mississippi and Washington.) These agencies are generally already set up to receive FAFSA data, liaise with the legislature and budget offices, and administer funds to students and institutions.

- Relying on general fund appropriations

Similar to the majority of existing state aid programs, existing state-level free community college proposals often rely on general fund appropriations as a funding source (i.e. Hawaii and Texas.) Echoing a common theme in state financial aid policy, H.B. 1733 in Oklahoma delegates the authority to the Board of Regents to ration dollars based on building additional student eligibility criteria into the program in case eligible students outnumber available dollars.

- Determining the award amount

State aid programs as they are currently constructed rely on complex institutional packaging processes that knit aid programs together towards the student’s overall cost of attendance. Within state-level free college proposals, the packaging process generally determines the award amount needed to make tuition “free.” Relying on the existing aid packaging process explicitly treats the free college program as a form of financial aid, not as a universal benefit.

Perhaps the most important difference between existing aid structures and free college proposals lies within the marketing. The use of the word “free” is proving to be a powerful choice, and one that proponents hope will incite students to enroll in a postsecondary program. What we’re seeing in state houses so far indicates we still have a long way to go before any legislation proposing a publically supported and truly universal college experience is considered.